Why You Should Use A Product Development Process

By David M. Giltner, TurningScience

Product development is one of the most exciting things we photonics technologists get to do with our training and experience. The excitement of designing and building things that others will use is very rewarding. This is even more true when the product is a brand-new solution, as is frequently the case when working in an early-stage technology company.

Roughly half of the 23 years since I began my career have been spent turning new technologies into products — a task that carries significant challenges, because there is no map to guide the development. Often, new products do not have well-defined requirements, because the target customers have never used such a device. While more developed industries may have multi-source agreements to define performance and reliability standards, teams developing brand new products often have to define these standards themselves — ideally, by working closely with intended customers for guidance.

Successful Teams Have Playbooks

Small teams working on new technologies have a tendency towards fast, but somewhat uncoordinated, development. Just like an informal game of American football, where a bunch of friends gather to play only occasionally, plays can be inefficient at best, and downright sloppy at worst. This is because, although each side believes they all are moving towards the same goal, plays often are made up on the spot and described ad-hoc in the huddle, seconds before the play.

This is why professional teams develop and practice a wide range of plays. When everyone knows the plan clearly, the team is much more coordinated in its efforts, players are more likely to be where their team expects them to be, and the outcome generally is much closer to what was intended.

A playbook generally helps with three key aspects of the team’s performance:

- Continuity — ensures all team members are running the same play

- Consistency — ensures that each time a play is run, it’s done the same way

- Communication — establishes a lexicon, ensuring that a particular play can be discussed without requiring a full description of the details every time it is referenced.

It’s much the same with product development teams. Early-stage technology companies tend to function more like the friends who gather to play football. While the teams may believe they are working towards the same goal, the players do not all have the same perspective on how the team will achieve that goal.

Like the informal football game, execution of that plan can range from inefficient to completely ineffective. Having a good product develoment system, often called a product development process (PDP), can help significantly.

The Product Development Process

Mirroring the way a playbook helps a football team, a PDP helps a product development team in three key areas:

- Continuity — ensures all team members are working towards the same product goals in a coordinated manner.

- Consistency — ensures that each time a product is developed, it is done with the same important steps and decisions.

- Communication — establishes a lexicon so product status can be communicated efficiently, without requiring a detailed status description each time.

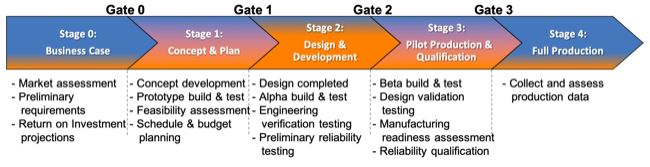

The sample PDP below — a “Stage-Gate” PDP (Fig. 1) — illustrates how this works. In this system, the product development cycle typically is broken into four or five stages, depending on the type of product and application. The activity in each stage is very different from the one before it, and the level of financial and/or resource investment generally changes dramatically at the transition.

Fig. 1 — Outline of the Stage-Gate PDP

Between each stage is a ‘Gate,’ a meeting where the senior management team reviews the program’s status against objectives and metrics defined during the program’s planning stages, and determines whether to continue. Thus, if the metrics are being met, the management team may elect to approve continued product development to the next stage; if the team is falling short of its stated objectives, management may elect to require additional work before proceeding, or choose to kill the project entirely.

As an example, suppose that gross margin targets were defined during stage 1 and, by the end of stage 2, materials costs have ballooned and gross margin is falling below the target. The management team may decide the product no longer makes good economic sense and should be scrapped. Alternately, the additional market assessment may show that the market is 30 percent less than projected, and the return on investment (RoI) calculations no longer meet the company requirements.

Simplicity Is The Key

Excellent references exist describing the Stage-Gate PDP’s details, so I will not try to recreate them here. Instead, I’d like to make a case for why I think all companies should use the Stage-Gate process, and why early-stage companies should consider starting right away. The PDP does not need to become ‘big company bureaucracy’ that creates lots of busy work, limits creativity, and slows progress. In fact, when done properly, it will do just the opposite.

Early-stage technology companies often pride themselves on being quick and agile, and this is a great thing. However, such companies must take note how often fast changes are made that don’t necessarily move the project towards the goal. Quick decisions, made by individuals without team coordination, can easily counter the quick decisions made by others and, without a strong system in place, the team may not even be aware. As the phrase credited to US military special forces states: “Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast” (i.e., careful and deliberate outperforms rushed and reckless).

Fig. 2 outlines a PDP that I suggest to companies with whom I work. This approach’s first benefit is it fits on a single page: I’m a big believer in single-page-systems, because if a team can create a visual depiction that fits on one sheet, it can be easily explained, remembered, and used.

Fig. 2 — Stage-Gate PDP outline with key deliverables for each stage

Second, each Gate lists no more than five key deliverables. I’ve seen companies grow Gate deliverables into a five-page checklist. This overkill is exactly what gives processes a bad name and keeps them from actually being applied to product development.

Third, the Stage-Gate PDP is intended to be a guide that ensures the team remembers the objectives and metrics they agreed were important at the program’s outset, and not to legislate the team’s every little move. If, at Gate 2, the team agrees it makes sense to move ahead despite not having achieved a goal — because, perhaps, the team has learned this market is different than they anticipated — that should be OK. Good leadership is as much about knowing when to break the rules as it is following them.

This leads to the fourth benefit of using a PDP: flexibility. Development teams are created to innovate, and they typically do this well. However, their capacity for innovation typically is finite, and spending such a team’s time and energy navigating a new development pathway every time they develop a new product is not a wise allocation of resources.

PDPs make it easy to repeat the things that previous teams decided worked well, so each team can focus its innovative will on the things that really matter: technology development, working with the customer, and making the hard decisions that inevitably arise during any project — those few things that don’t fit the precedents set on previous projects.

Applied poorly, systems turn into bloated regulations that no one trusts or uses effectively. Applied properly, the right systems improve the efficiency and effectiveness of product development teams.

About The Author

David Giltner is the author of the book Turning Science into Things People Need, and the founder of TurningScience. He is an internationally recognized speaker and mentor for early career scientists and engineers seeking careers in industry, and works with early-stage technology companies to help them turn their inventions into successful products. He has spent the last 20 years commercializing photonics technologies in a variety of roles for companies, including JDS Uniphase and Ball Aerospace. David has a BS and PhD in physics and holds six patents in the fields of laser spectroscopy and optical communications.