Submarine Cables, The Black Sea, And The War In Ukraine

By John Oncea, Editor

Russia has been making the argument that it’s their right to destroy “the ocean-floor cable communications of our enemies.” So, how safe are the nearly one million miles worth of submarine cables, particularly those in the Black Sea keeping Ukraine up and running?

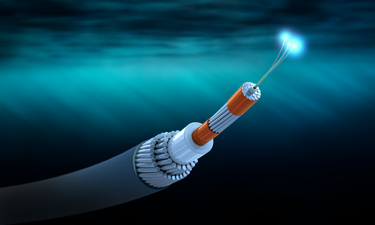

Nearly 950,000 miles worth of submarine cables – fiber optic cables that carry telecommunication signals across stretches of the Earth’s oceans – are out there, connecting countries across the world. These cables are known for their ruggedness, designed to withstand conditions that can break or interfere with their function including shock, varying temperatures, chemicals, pressure, and of course, water.

Having been around since the 1850s, submarine cables are now responsible for 95% of international data, as well as the subject of a battle for control between the U.S. and China. But there’s another battle brewing over submarine cables, this one taking place in the Black Sea where cables could be disrupted by the fighting in Ukraine.

Back To School: Submarine Cables 101

“The submarine cables that move internet traffic around the world are made from silica glass fiber optic strands that most network engineers are likely familiar with,” writes Kentik. “However, submarine cables need to allow light to travel very long distances with minimal attenuation, so the G.654 subset of fiber is used for undersea applications.”

The use of Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing (DWDM) in cables allows large amounts of data to be moved by simultaneously sending different data streams using multiple wavelengths of light over a single fiber infrastructure. Submarine optical fibers are usually single mode, with G.654A-D being a common type that has better attenuation compared to most land-based fiber optic cables. G.654E fibers belong to the same family of fibers but are typically used for unique land-based applications that require even lower-loss fibers.

As of earlier this year, there were 552 active and planned submarine cables, according to TeleGeography. That number is constantly changing, of course, as new cables are deployed and older cables are decommissioned.

“For most of its journey across the ocean, a cable is typically as wide as a garden hose. The filaments that carry light signals are extremely thin — roughly the diameter of a human hair,” writes TeleGeography. “These fibers are sheathed in a few layers of insulation and protection. Cables laid nearer to shore use extra layers of armoring for enhanced protection.”

Fiber-optic technology is commonly used in modern submarine cables. Lasers emit at high speeds from one end of the cable, traveling through thin glass fibers to receptors at the opposite end. To ensure durability, the glass fibers are coated with layers of plastic and occasionally steel wire.

Cables that transmit data across the ocean are typically buried under the seabed near the shore to protect them which is why you don't see them when you go to the beach. However, in the deep sea, they are laid directly on the ocean floor where great care is taken to ensure they are placed in the safest possible path to avoid fault zones, fishing zones, anchoring areas, and other hazards.

“Cables were traditionally owned by telecom carriers who would form a consortium of all parties interested in using the cable,” TeleGeography writes. “In the late 1990s, an influx of entrepreneurial companies built lots of private cables and sold off the capacity to users. Both the consortium and private cable models still exist today, but one of the biggest changes in the past few years is the type of companies involved in building cables.”

Companies like Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and Amazon, which provide content, are investing heavily in new submarine cables. Private network operators, including these content providers, have deployed more capacity than internet backbone operators in recent times. Given the likelihood of significant bandwidth growth, having ownership of new submarine cables is a logical move for these businesses.

There are, on average, over 100 cable faults every year but the companies that use them spread their network’s capacity of multiple cables to ensure that, if one breaks, their network stays up.

“Accidents like fishing vessels and ships dragging anchors account for two-thirds of all cable faults. Environmental factors like earthquakes also contribute to damage,” writes TeleGeorgraphy. “Less commonly, underwater components can fail. Deliberate sabotage and shark bites are exceedingly rare.”

Trouble Brewing In The Black Sea

About that sabotage …

The Conversation writes that “former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev argued recently on his Telegram channel that Russia should have the right to attack submarine data cables. Medvedev claimed such rights against the background of recent media reports on the mysterious sabotage of the Nord Stream undersea gas pipeline last year.”

Specifically, Medvedev wrote, “If we proceed from the proven complicity of Western countries in blowing up the Nord Streams, then we have no constraints – even moral – left to prevent us from destroying the ocean-floor cable communications of our enemies.”

Whether an actual threat of political theater, such an act could potentially create chaos for Ukraine and its neighbors.

“As fighting rages on in Ukraine, the cables in the Black Sea could be in danger of disruption,” writes the Middle East Institute (MEI). “Accidents have caused damage to the cables in the past, and stepped-up naval activity in the region could raise the risk of vessels accidentally cutting the lines lying on the seafloor.”

Beyond accidents exists the threat of a deliberate Russian attack on these cables, keeping in step with the Kremiln’s strategy of “targeting critical infrastructure to gain strategic advantage without necessarily delivering decisive blows against its enemies.” These could be cyberattacks or physical destruction.

Such an attack wouldn’t be unprecedented, notes MEI, citing a Russian hacker attack on Ukraine's power grids shortly after the annexation of Crimea. “While Ukrainian authorities could not present indisputable evidence implicating the Kremlin, many believe the cyberattack was a carefully orchestrated operation involving the Russian state and cybercriminals.

“The attacks on Ukrainian energy infrastructure have escalated since Russia’s full-scale invasion began on Feb. 24, 2022, ranging from cyberattacks to shut down energy companies’ systems to military strikes on key facilities, triggering widespread electricity outages across Ukraine and Moldova.”

The impact of an attack on submarine cables is purely hypothetical at this point as there has yet to be a definitive act of sabotage so far. However, some defense officials have speculated that Russia could employ the same tactics used during the 2015 attack on Ukraine’s power grid, coordinating with adversary states to hide their involvement.

“Furthermore,” writes MEI, “Russia has been investing in capabilities that would allow specialized submarines to place explosives on the seafloor, physically endangering underwater communication infrastructure.”

In addition to the Russian navy, Russia’s Deep-Sea Spetsnaz — the Main Directorate of Deep-Sea Research (GUGI) — can act as well. “North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) officials suspect that GUGI has been increasingly focusing on undersea cable networks in recent years,” reports MEI. “Notably, in January 2022, Norway detected damage to one of two fiber optic cables off the Svalbard archipelago; suspicions that the cable disruption may have been intentional grew later that year after a mysterious explosion crippled the underwater Nord Stream natural gas pipeline, an incident that is still under investigation.”

What To Do

MEI notes there has been limited movement in protecting submarine cables, starting in 2017 when current British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, then a member of parliament, “published a report analyzing threats to the global submarine cable network with proposed recommendations for how to protect them. Among his proposals, Sunak suggested that NATO increase naval exercises and wargames designed to improve protocols and capabilities in response to sabotage of undersea cables.”

In 2020, NATO defense ministers emphasized the need to identify potential threats to submarine infrastructure, specifically from the Russian Navy. To increase security measures, NATO assigned Joint Force Command Norfolk (JFC-NF) to watch over and defend these networks in the Atlantic region. It may be beneficial to implement a comparable mission plan in the Eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea areas to safeguard NATO’s exposed southeastern flank.

If Russia were to follow through on its threats to cut undersea internet cables, the primary economic impact would be the cost of repairs. However, relying solely on a military approach for protection would not be sufficient.

“Close collaboration between the military, civil maritime agencies, communication regulators, and the industry is needed.,” The Conversations writes. “The European Maritime Security Strategy expected to be issued by the European Council this summer will be an important step in this direction. The strategy lays out plans for risk analyses, improved surveillance, and inter-agency exercises.”

Further complicating matters other maritime infrastructures – wind farms, power cables, hydrogen pipelines, and carbon storage projects – are also vulnerable and in need of the same considerations and protections. These are all driving the modern world in which we live today and, should something go wrong, it would have a massive effect.