Role Call: Consultant Engineer

Is the grass truly greener on the other side of the fence? You never know until you peek over it.

Role Call is a new series on RF Globalnet that will look at different jobs and career paths in the RF and Microwave industry. We’ll explore what each position entails, how much you have to know, and what experience you need to get started.

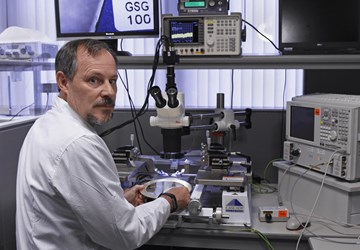

The first position we have explored is a consultant engineer. Andy Dearn, the Principal Consultant Engineer at Plextek RFI Ltd., let us take a peek behind the curtain, revealing everything from the most exciting aspects of his job to the mundane day-to-day activities.

What does your position as a consultant engineer currently entail?

I currently spend most of my time designing GaAs and GaN Monolithic Microwave Integrated Circuits (MMICs). The company I work for, Plextek RFI, is relatively unique in that we don’t sell standard products, we sell our design time. Most of our designs are application-specific, to suit exact customer requirements.

I’m also now involved in some marketing activities, and I produce all of the technical videos on the Plextek RFI YouTube channel.

How has your position changed or evolved over the years?

Design timescales are much shorter nowadays. When I first started doing MMIC designs in 1987, everything was done using small-signal S-parameters only. This soon progressed into full non-linear designs (harmonic balance, etc.), and I now spend a lot of my time doing full EM simulation on IC layouts.

What was the education required for this position, and what are the continuing education requirements?

A relevant degree in electronic engineering or physics is essential, plus practical experience on relevant design projects. Our business is based on selling design services, and we need engineers who have solid experience in a commercial environment.

When I graduated in 1985, there were very few universities offering specific courses in microwave engineering. My degree is in physics, and on graduation I was employed by Ferranti on the basis of my knowledge in electromagnetics. My expertise in microwave technology has all been acquired in the course of my job.

I’m a Chartered Engineer and a member of the Institution of Engineering and Technology (IET), which is similar to the IEEE. Continuing professional development (CPD) training is now mandatory to retain these qualifications. It is relatively simple to monitor and record learning experiences on the IET’s CPD website.

What experience did you need for your position? How long did it take you to reach the skill level that you are at now?

When I began my career, I had no knowledge of S-parameters or the Smith chart. I basically taught myself the basic skills of RF and microwave engineering with on-the-job training. Within about six weeks of starting work, I was designing X-band VCOs on one of the very first versions of EEsof’s Touchstone CAD program. I would say it was around two years before I was convinced that microwave circuits obeyed the laws of physics, rather than black magic. I have now been a design engineer for 32 years. It’s a continuous process of learning, so it has really taken me all of those years to reach the level I am now.

What types of things did you need to learn on the job?

As mentioned I had to learn S-parameters and Smith charts the hard way! Then, [I had to learn] use of the design and simulation software, which has developed continuously over the years. We currently use ADS from Keysight, which is a very comprehensive software suite. In the early days of my career it was netlist entry only, and we could only perform small signal simulations, often using transistor S-parameters, rather than models. Now, we can often work with accurate large-signal models and undertake full EM simulations. However, there are still many instances where we need to develop or enhance our own models for specific purposes.

MMIC layout is another skill that I learned on the job. My first designs were often simple single-function components, but today we design and lay out complex, multi-function MMICs operating at mm-wave frequencies, for applications such as 5G or radar.

What does a typical day in your position look like?

I tend to boot up ADS and run some quite complex harmonic balance and EM simulations throughout the day. I also have to document all aspects of the design process for our clients. Most of our projects have preliminary, critical, and final design reviews at various stages of the design cycle. At the end of the design and manufacture phase, I am also involved in the RF-on-Wafer test of the MMICs.

As our company is relatively small, I also get involved in marketing activities, such as preparing content for the company website and organizing logistics for the IMS exhibition.

What are the biggest challenges that your work presents for you?

All of our clients understandably want the lowest noise figure and highest power-added efficiencies in the smallest possible die size – it’s very rare we’re asked to design anything straightforward. The time required to EM-simulate and optimize the design and layout of a high-performance mm-wave MMIC can be considerable, because great care and attention to detail is required to get everything right.

What specifically drew you to this career path?

I always wanted to design electronic gadgets of some sort. I find high-frequency and wireless stuff much more interesting than conventional low-frequency analog or digital electronics.

What is your favorite part of your occupation?

I actually prefer the layout side of MMIC design. You can get quite ‘arty’ in this aspect of the job. It’s also incredibly challenging to lay out a mm-wave IC in the most efficient way. I still believe fully-automated layout is a long way off in the RF and microwave world.

We all have interests that are separate from work. What hobbies or other interests do you have outside the office?

I’m a very keen amateur photographer. If anyone is interested, they can view my work on Flickr or Instagram.

I’m also very keen on rock and pop music, but unfortunately have no talent for playing musical instruments. In the unlikely event that Dave Grohl is reading this, I would be very interested in some Foo Fighters tickets for the upcoming London gig!

Based on your lecturing experience at Oxford University, what advice would you give to an individual just starting out in this field, both in terms of component design and professional development?

I would advise taking the time to learn every function and shortcut key in your chosen CAD package. I also advocate simulating high-frequency components in as many ways as possible. For example, when designing oscillators, you should check the performance in both small-signal and transient test benches, as well as the more obvious harmonic balance bench.

If your day job is designing power amplifiers, for example, take the time to learn oscillator and mixer analysis techniques. The oscillator design skills give you alternative techniques for ensuring your amplifiers are unconditionally stable. Three-port mixer techniques can help with the understanding of multi-tone amplifier simulations.

If you’ve ever wondered what a day in your RF dream job looks like, or you just want to discuss a job you’re passionate about, contact the author at mstonefield@vertmarkets.com with story suggestions, or to volunteer as a Q&A subject.

About the Author:

Marissa Stonefield is a Web Content Specialist for Photonics Online, RF Globalnet, and Med Device Online. She graduated from Messiah College with a B.A. in marketing, and from the Community College of Beaver County with an A.B. in business administration. She has previously worked as a content writer for Vanko Trading Inc., and as a journalist for Examiner.com, and Weddings Year Round Magazine in Lancaster, Pa.

Marissa Stonefield is a Web Content Specialist for Photonics Online, RF Globalnet, and Med Device Online. She graduated from Messiah College with a B.A. in marketing, and from the Community College of Beaver County with an A.B. in business administration. She has previously worked as a content writer for Vanko Trading Inc., and as a journalist for Examiner.com, and Weddings Year Round Magazine in Lancaster, Pa.